First, get yourself born and raised in Southern California, preferably in the San Fernando Valley (the one that Valley girls come from). Next, attend Grant High School at the corner of Coldwater and Oxnard, making sure to associate with all the soon-to-be hot players in their formative years. Then, when you're in your ripe old teens, get invited along on a big-name rock star's tour in support of his biggest album. Help out on the tunes and replace the existing lead player. When you return, have your phone ring off the book with studio calls and organize a supergroup that Columbia Records makes a huge offer to before even hearing it, before it's really even formed, because of the reputations of the aforementioned hot players. Use a cute name that's easy to say and easy to remember. Have the first album go platinum on the basis of a monster hit called Hold the line. After three albums of diminishing succes, win a truckload of Grammys for the fourth album and your work on other people's hits. Last and certainly least, invite journalists into your spacious home in the hills above the 'good' side of Ventura Boulevard, so they can wonder if maybe they should have practiced more.

'Well, it's wasn't quite that easy,' says Steve Lukather, guitarist and songwriter for Toto. 'But I mean it wasn't that hard either. Let me tell you about the due I paid [laughs, emphasizing the singular]. I did play at bars, at fraternity parties dodging beer bottles, that sort of thing. And I was discouraged for quite a while, thinking, 'Wow, is this it? Is this all that there's going to be?' And all of a sudden, it was almost, like, overnight.'

Overnight began when Steve began playing at age seven (he's twenty-five now), drawn to the music of his father's Beatles albums. His first guitar was a Kay acoustic, 'a piece of shit'. 'The strings were five feet off the neck and that sort of thing. I played that for a couple of years and then I had an Astrotone guitar from Thrifty's. I didn't really have any formal training till later, but I had the Mel Bay book you know, 'this is the pick'. That's where I learned a lot of my chords. I didn't start studying till I was sixteen, when I studied with Jimmy Wyble. He's amazing, just a wonderful guy. I haven't seen him in a couple of years, but he really helped me so much. He opened my ears to a whole other approach. I didn't know anything about music at all. I was just basically a slam-bang hard rocker, you know, pentatonic scales and shit. I didn't know a half note from an eighth note, and because I could already play one way, it was hard to go back and learn another. Sight-reading Mary had a little lamb was kind of frustrating. I wasn't exactly the greatest student in the world at first, and Jimmy Wyble was very very patient with me.'

The slam-bang stuff came from records by Clapton, Hendrix, et al. What about the impetus for serious study?

'I got hip to some of the studio players, like Larry Carlton, who was a major influence. Through him, I met Jay Graydon, another major influence. And that opened up a whole new concept of playing, other than just the slam-bang stuff, which I still enjoy.'

And how long did it take for the young hopeful to make his first recording?

'[laughs] Oh, I was about eleven. If you were to hear it, it would really be funny. It never came out, but it was actually put on a record. It was just a power trio thing. Fuzz tone, wah-wah pedal, cheap blues licks and stuff.'

It was one of those what-you-know, what-do-you-know situations that led to Lukather's first legit recording, an album by Terence Boylan. 'I was really flipped out. I was on the same record with Dean Parks and some other great players. I was because of my affiliation with the Porcaro's and David Paich [now Lukather's co-members in Toto] and stuff like that. This was before we got the band together. My first real gig was when I was nineteen, when I went out with Boz Scaggs in '77. And that was incredible. Right before that, I was working with Jai Winding on a rehearsal band type thing. We had just gotten off the road with Jackson Browne. We just met each other and he liked my playing. He was doing the Boylan album and recommended that I play on it. Then I went out with Boz and then we got the Toto thing started, and then from that, I got called to do a lot of sessions because everyone heard I was in a band with those guys. That really helped a lot.'

The Boz Scaggs gig came about in approximately the same manner. 'It was because Jeff and Steve Porcaro and David Paich were playing for him. David wrote most of his songs on Silk Degrees. Les Dudek was in the band at the time. And Les had bailed. So I was there and it was really happening. Boz was doing very well and I had a chance to write some stuff. It was great being nineteen years old, all the big time rock and roll, private planes, limousines. I went from, like, one extreme to the next, being that young, being out on the road, making some decent money. I said, 'Shit! I can do this for a living!'. I mean, I've been real fortunate in my life. I really have been very fortunate - the right place at the right time, that sort of thing.'

One of the right places has been the studio, where Lukather has done sessions for many other artists, like Randy Newman, Paul McCartney, Donna Summer, George Benson, Quincy Jones, Lionel Richie, Michael McDonald, The Tubes and Herb Alpert, to name but a few. 'When I first started doing sessions, I was doing those kind of dates where it was like the reading end of it. I can read, but I'm no Tedesco - Tedesco's a genious. Mostly the stuff I get called for is, like, 'fill in the blanks.' Like, you see an A chord for twelve or sixteen bars, come up with something that makes sense. Which is what I guess I do best. You know, out of all the studio things. Or people call me up to play solo once on something. I was on the kind of stuff you have to bite your fingernails on on the way to the date. I've done a couple fo those just to humble myself, man. A couple of jingles and a couple of movie things. It's like, you know there's a God because he got you through it. The last commercial I did was Made in the shade jeans. That was a couple of years ago. I said, 'Man, this isn't for me.' It's a different vibe altogether. I'm lucky enough to have a choice in the matter. I prefer just doing rock groups, because it's what I do best. I'll leave that other stuff for the guys who really know their shit. Records are basically my thing.'

WHAT ADVICE does Luke have for the guys who DO want the reading dates? 'People they go, 'hey man, I'm new in town. How do I get into the studio scene?', and I go, 'Jesus, man, I don't really know. I mean I went to high school with the cats.' That's how I got the opportunity. There's no set way to get into that. If there is, I could write a book and make a million bucks. But there isn't, man. It's a matter of being at the right place at the right time. Having the right attitude. Attitude is very important, as is protocol. Like, if you sit next to another guitar player without realizing it. You know you don't sit next to Tommy Tedesco and step on is toes, or kiss ass or shit like that. People don't dig that. Just being able to play good and not overplaying, playing what's necessary and really trying to make yourself an integral part of a good session by coming up with a really good part that's really simple but helps the tune out. It means being on time and just being a nice cat. It takes a while. If you have a horrible experience, it doesn't mean you career is over. You know, if you blow it, you can't read a part or something. It's happened to some of the greatest. What you do is fake a heart attack and bail. You make yourself throw up, say you've got the flu and you go home. You never cop to the fact that you can't read the part. You just realize that maybe you should practice for a while longer or decide that you don't really want to do that kind of studio work. It's a slow process once you get in. You'll get a call and maybe it comes off good. And maybe you won't get a call for a while. Or you hear about a date going on with the same cat and he didn't call you. You get real paranoid. You say, 'Oh fuck, I blew it. I'll never get work again in this town!' But eventually… it's like a comedy of errors. And pretty soon, people start talking about you and you gain a reputation. And that's how you get the opportunities.'

In a career full of opportunities and high points, one of the highest for the guitarist has been meeting and working with Paul McCartney. 'He's the nicest, most wonderful cat you've ever met in your life. The Beatles were the reason I started playing, and he was like everything you wanted him to be. He's a really nice guy, a really great musician, a really great attitude, a really smiling happy guy. I couldn't help it - I kept staring at him. I guess he's used to it. But he just smiles and goes, 'yeah, yeah, nice part.' And I'm thinking, 'Jesus! Who the fuck am I? I could die right now to be cool.' I was in awe of the cat. For real. Jeez, if it wasn't for him, rock and roll would never have gotten to the point where it is right now. It was amazing, such an honor I can't even say. Jeff and I are going to London in a couple of weeks to cut tracks with George Martin and Paul, and actually be in his movie. I think it's going to be called A day in the life.'

Another high point, of course, has been Lukather's partnership in seven Grammys. With all the attention, isn't the heat really on for the next album?

'You would think, and I suppose to a certain degree, it's subliminal. But we're just going to go in and approach it like we would normally approach a record. We're trying as hard as we can. I think we've got some great new tunes. And I think we're going to follow through with it. We usually take a lot of time with our records, because we cut about twenty tunes and then pick the best from those. For us, the Grammy was an incredible honor. Especially considering considering what our competition was, Donald Fagan's solo LP. His album was an incredible album. It's an honor.'

Viewers of the Grammy Awards telecast may have noticed Toto's tongue-in-cheek expression of gratitude to one Robert Hilburn. Hilburn is the chief pop music critic for the Los Angeles Times and has long been one of the band's detractors. It's become very popular among critics to use the word 'faceless' in gainsaying groups like Journey, Foreigner, Asia, and Toto.

'Yeah, the funny thing is that those bands all have good musicians in them. The bands they like are the Psychedelic Furs and the Clash and that sort of thing. Those guys aren't really that great of players, I don't think. But that's not fair. It's just my assumption, being that I don't go out there and listen to their records a lot. Hilburn is not a musician, he knows nothing about music. He has no credentials whatsoever to be where he's at. And he's just cruel, you know, for no reason at all. It's really kind of stupid that we even acknowledged the fact that he exists. I figured if we won something we owed him a jab. It was real subtle, you know. It's just that two hundred million people saw it. Everyone in L.A. laughed when we said that, so it probably got to him [A Hilburn article about the jab appeared in the Times a week later ]. It can get really frustrating sometimes. It's like the better you play, the more they hate you. Which to me is rather bizarre. You know what I mean?'

The Lukather ax arsenal consists mainly of a '59 Les Paul and a bastardized Stratocaster with Floyd Rose tremolo system and EMG pickups. 'And I'm using some Ibanez guitars too. I just recently designed something for them. It's nothing like, 'Oh, wow, it's going to change the face of the music industry,' but it's kind of new, and I'm excited about it.'

And effects? 'The guy who works with me, Dick Gall, designed my pedal board. It's a complete stereo system, an A/B system, both clean and dirty. I'm using an Eventide Harmonizer, four digital delays, two Roland chorus echoes, a DBX stereo compressor and limiter, two Ibanez multi-effects units, an API graphic equalizer out of a regular console. Oh God! Tons of stuff! And I have about eight or nine amps, but the ones I mostly use are two 100-watt Marshalls that have been customized by Paul Rivera. And two black-faced Deluxes that I use in stereo that have been modified by Paul as well. And I have some old 50-watt Marshalls and an Ampeg BT22. And I have an amp that Howard Dumble built for me that I use for cleaner things. It's got that warm sustain.'

What about these players that live in Wyoming or Kansas or anywhere else? What should they do?

'Hang in there, man. Because just when it looks real bad, like it did for me, all of a sudden something great is going to happen, if you just hang in there and practice and you're real serious about what you're doing. I mean, it's okay and a lot people do it for a hobby, which is cool, man. Music's fun. But if you really want to be serious about it, it's a long hard process. And I'm not just talking about gigs and stuff. I'm talking about getting to the point where you're good enough to do gigs. Nobody likes to practice eight hours a day, but that's what it takes, man. You should evaluate if that's really what you want to do, then you've got to do it. You have to give up something to get something. That's usually the case. I was very fortunate and maybe sometimes other people are not so fortunate, but that doesn't mean it's not within their grasp.'

And what does the future hold for the guitarist, singer, songwriter and producer?

'I imagine Toto will be together for a long time, because if we haven't broken up by now, we ain't going to. But, maybe in a few years, I'll probably do a solo record or something. I would never leave the band, so it would just be something I would do off time, just for fun. Not to start a career on my own. I know that I really need to be in the band, because those guys got the best out of me. And I really feel like an integral part of it, so why leave something that you're really happy with? And I love all the guys. We're all best friends. It's not like we're a bunch of egomaniacs who hate each other, like, 'I'm not going into the studio until he leaves,' and that sort of thing. And you'd be surprised at the bands that do that. Real surprised. Everybody wants to be the star and all that shit. I suppose that's the advantage of having a faceless band like ours. We're not a bunch of pretty boys. We're just a bunch of musicians that play pretty good and like making records and making music.'

The entire band's equipment weighs over twelve and a half tons and takes three semis to haul around. 'I love the road, man. We're not one of those party bands. I don't say we never party, but not in the sense of total bodily abuse. You can't party too much on the road, because if you do, you're traveling every day. And man, you have to keep your health up. Because if you get sick on the road, then you have to start cancelling gigs and stuff like that, and then it costs you so much money. We lost two hundred fifty G's on our last tour, but we were able to make it up on record sales. It's expensive carrying all that gear, but we want to make our live sound as good as our records.'

In addition to working on Toto's next LP at David Paich's home studio, affectionately known as Hog Manor, and getting ready for his silver screen debut in the McCartney film, Luke is co-producing an album by Tom Kelly and Billy Steinberg. The word 'producing' seems to change meaning with each producer, and to Steve Lukather it means, 'You're there from the inception of the project, you pick the songs, and if you're a musician, you arrange the songs pretty much. And you help write some of the material as well. You pick the takes, the take of the track. Or if you don't like it, you try the song, and you say, 'No, we shouldn't need to do this again.' You reevaluate it, rearrange it. Try another concept or recording techniques. And then there's tricks and stuff like that to get different sounds and knowing the entire process of recording, like from an engineering standpoint as well as from just an objective ear. And you have to try and get a performance from somebody. Like a vocalist. Inspire them, not saying that they sound like a broken pig in heat or something like that, you know, for singing bad. You just have to be an inspiration and know how to put it together. Like, you take a vocalist and you'll do four tracks of vocals. And maybe you don't have the take with one whole pass, so you have to patch them together. You have to know what that is. It's not necessarily the pitch and stuff like that, it's just the performance. And following it through to the very end, like the mixing process, making sure that it comes out the way that it was intended. Or better.'

Being surrounded by great musicians in the band, in the studio and in the city of L.A. at large, Lukather has managed to single out some favorites. 'There are a couple, man. There's my friend Michael Landau, who's with Joni Mitchell. We grew up together, playing together. He's a great player. And besides the people I mentioned previously, the Carltons and the Graydons , there's a new kid in town. His name is Jimmy Haun. He plays in a group called logic. They're a local band. This kid, he's a lefty, and he is fucking hot! I'm trying to get him some gigs and stuff, because he is really good. I haven't heard anybody that's knocked me out like this guy in a while. He's got the fire. He's a young kid, about twenty-four. And such a nice guy. He's like working in an electronics store. And I'm going, 'God, man, this guy should be playing!'. Besides those, there haven't been too many. I love Eddie Van Halen's playing, and Allan Holdsworth and that sort of thing. But everybody loves those guys, 'cause they're great. And guys like that should be heard. I'm lucky. I mean, I know I can play, but I've been lucky, because there's a lot of great players out there that people don't get a chance to hear because they live in Wyoming or something like that. They just don't have the bucks to get out here. Or if they come here, they don't know who to call.'

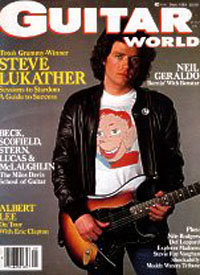

Guitar World, September 1983